“When it comes to researching the human brain in order to control emotions using AI, music and politics are very much alike.”

— Jerry Egan

It’s been fifty years since humans colonized Mars. Cities akin to Tokyo and New York are populated with first and second generation natives and an array of immigrants from Earth. Technology crowds every facet of life. From streets to homes, an android or robot pet is commonplace. Thanks to artificial intelligence, people don’t have to burden with working, thinking, or even creating anymore. “99% of modern hits are produced by AI,” a record producer tells an up-and-coming idol. Doing anything without a technological assist is an oddity.

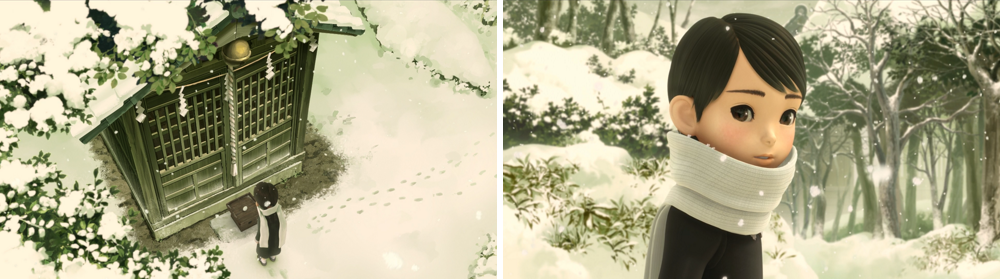

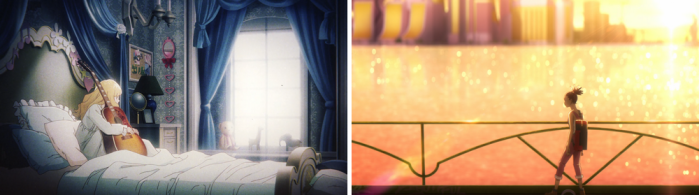

There are still people who prefer doing things the old-fashioned human way. Tuesday Simmons, a 17-year old from the lowkey Hersell City, dreams of becoming a musician. Fed up with the sheltered life under her strict mother, politician Valerie Simmons, she runs away from home with just a suitcase and Gibson guitar in tow. She arrives on the bustling streets of Alba City, and her suitcase is immediately stolen (never turn your back on your stuff in a big city).

On a sunset lit bridge—lost, penniless, and alone—Tuesday encounters Carole Stanley, a street musician who appears to be the same age as her. Carole’s upbringing wasn’t as cozy as Tuesday’s. A refugee from Earth, she grew up in an orphanage, and struggles with odd jobs as a young adult. Carole’s melancholic lyrics resonate with Tuesday in her moment of desperation. The two form an instant camaraderie as if by fate, and Carole takes her in.

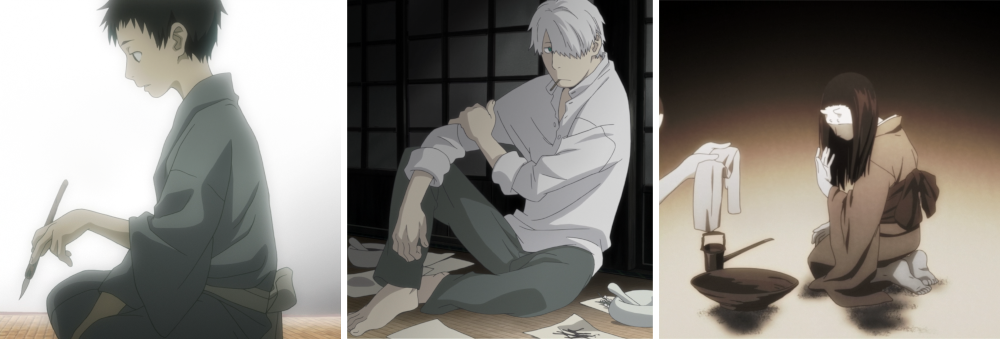

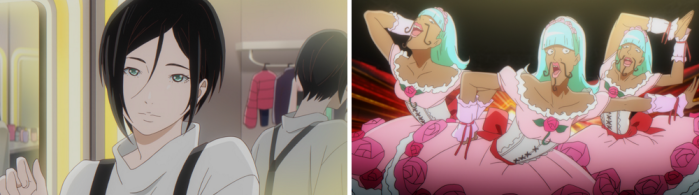

In a parallel story, Angela Carpenter, a 16 year old with excellent hair, already has a career as a model and actor. At the behest of Dahlia, her mother and manager, she works with a misanthropic technologist named Mr. Tao to start a music career. Mr. Tao prefers working with technology over people. His algorithmic approach to producing music is juxtaposed with Carole and Tuesday’s from-the-heart approach. At this point, it’s unclear if Angela’s new path is something that she wants, or if she’s doing it for her mother’s sake. Regardless, she doesn’t take kindly to competition, and she has a strong desire to be the best in everything she pursues.

The first 12 episodes, generally, had a casual slice of life vibe. It was so casual in fact that I worried if the story could stay fresh for the 24 episodes that were listed. On the other hand, I was hoping that needless drama wouldn’t be interjected to justify the runtime. Mercifully, with the exception of a few brief arcs (I’m looking at you Cybelle), the story neither dragged nor irritated me for too long. Strong worldbuilding, unexpected predicaments, thought provoking ideas, and bits of backstory kept each episode feeling new.

After a string of light-hearted, and often hilarious, performances and competitions, the story took an unexpectedly dark and political turn, touching on real world issues like convenience verses privacy, and the morality of using technology to read and influence people. The same technology that’s used to produce hit music is being used by politicians to improve their poll numbers. Data is collected from facial and sentiment analysis to tailor messages that will resonate with people. This is an interesting prospect because something like this will likely happen, and is already happening to a less advanced degree today.

Valerie’s presidential election, advised by the perpetually shady looking Jerry Egan, opens a discussion on another real world issue, the immigration debate. One side feels that a country (or planet) has a moral obligation to help refugees, and the other side feels that unfettered immigration poses a security and economic threat; Valerie sides with the latter.

There was also commentary on the struggle for human relevance as technology renders us irrelevant, and how neither pursuing our personal ambitions nor attaining societal acceptance can guarantee happiness. It was surprising to see such weighty topics in what I’d expected would just be a cute music anime. Shinichiro Watanabe (previously Cowboy Bebop) clearly had a lot that he wanted to say.

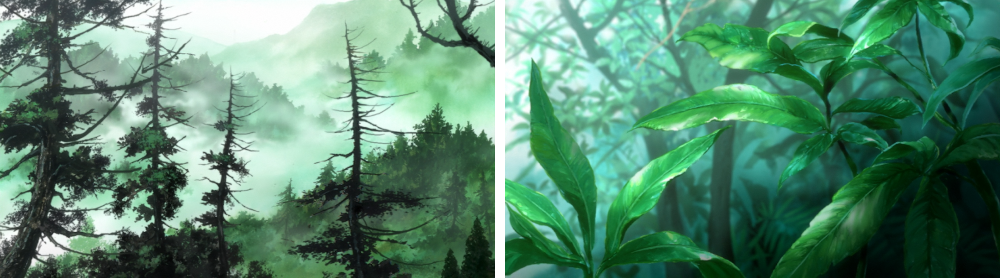

The animation by BONES studio shined. The art had a 90s aesthetic with a modern digital polish. Collectively, the cast had an extensive wardrobe, and the character designs were attractively detailed with highlights, shadows, and full lips. It would’ve been cool if those lips were always synced to the singing, but doing this likely would’ve exceeded their, presumably, already large budget.

The vinyl record eye-catches, printed with song titles that mirrored the theme of the episode, were a nice touch. Pop music isn’t a genre that I’m intimately familiar with, so I can’t give an unbiased assessment of the soundtrack itself. Regardless, I did love a few of the songs, especially the first ED. It was a delightful bop that I never skipped.

There were notable and instantly recognizable seiyuu surprises like Hiroshi Kamiya (previously Koyomi Araragi) as Tao, and Megumi Hayashibara (previously Faye Valentine) as Flora. Carole (voiced by Miyuri Shimabukuro) and Tuesday (voiced by Kana Ichinose) were voiced by actors with relatively short filmographies, but both filled their roles more than adequately.

I’ve been watching anime on-and-off for about 24 years (wow, I didn’t realize it was that long until I did the math). In that time, I’ve become less critical of the medium. If I’d seen Carole & Tuesday when I was a 20 year old film elitist, I’d likely rip apart how little friction the leads had to endure (despite enduring enough), how abruptly some turning points happened, and how briskly the last few episodes wrapped up the story—which are all valid criticisms. Today, at the ripe old age of 38, I’ve become a “filthy casual” in the way I watch things. While maybe not all of my expectations were met, I was more than satisfied by what was, for me, an uplifting and inspired experience.

Thank you, Shinichiro Watanabe.