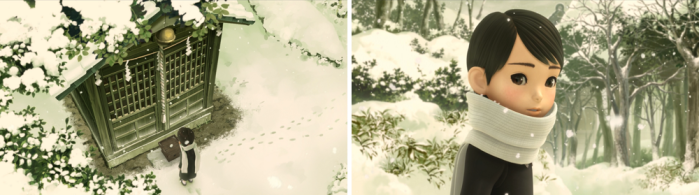

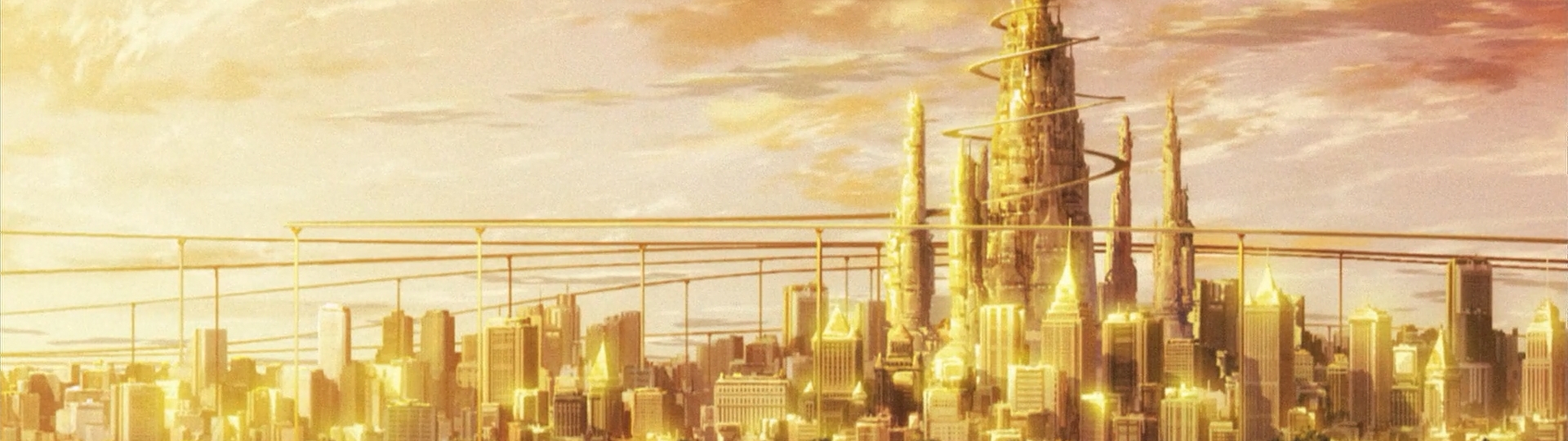

Haruka and the Magic Mirror is a 3D computer animated movie based on a Japanese legend of a trickster fox who collects people’s forgotten belongings. When Haruka, the plucky 16-year old protagonist, loses a precious mirror that her mother gave her as a child, her search for it leads to Oblivion Island, a hidden world full of magic yielding creatures and gorgeous scenery porn.

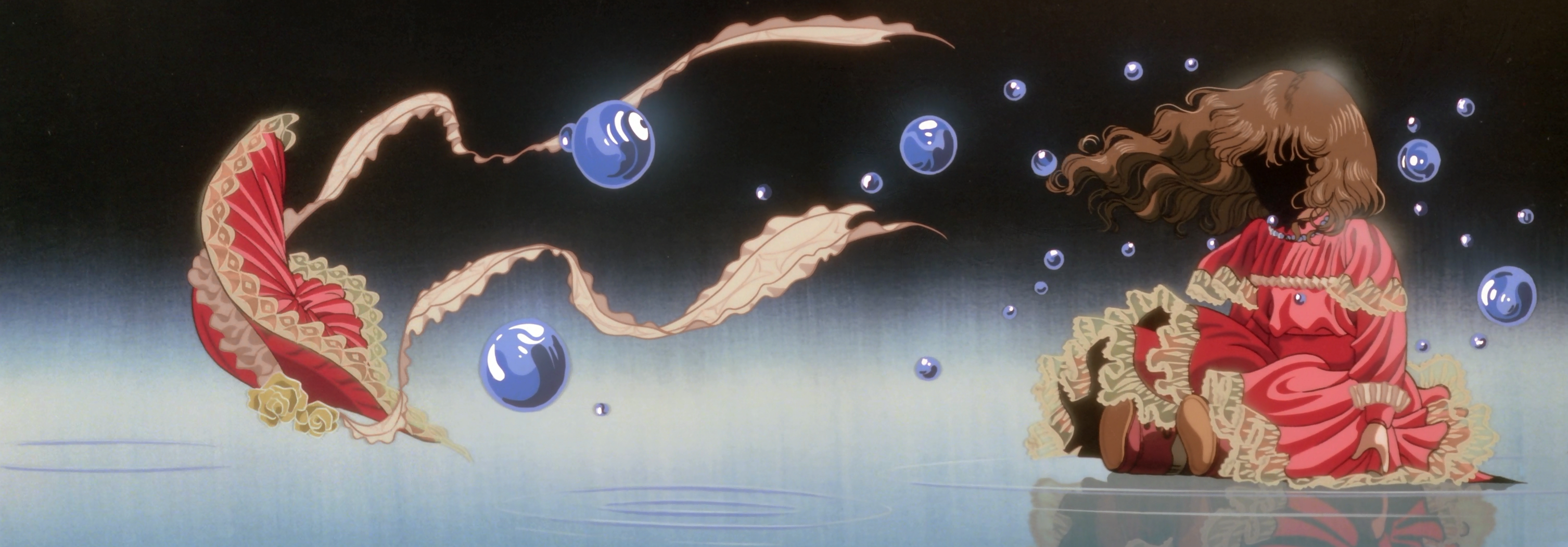

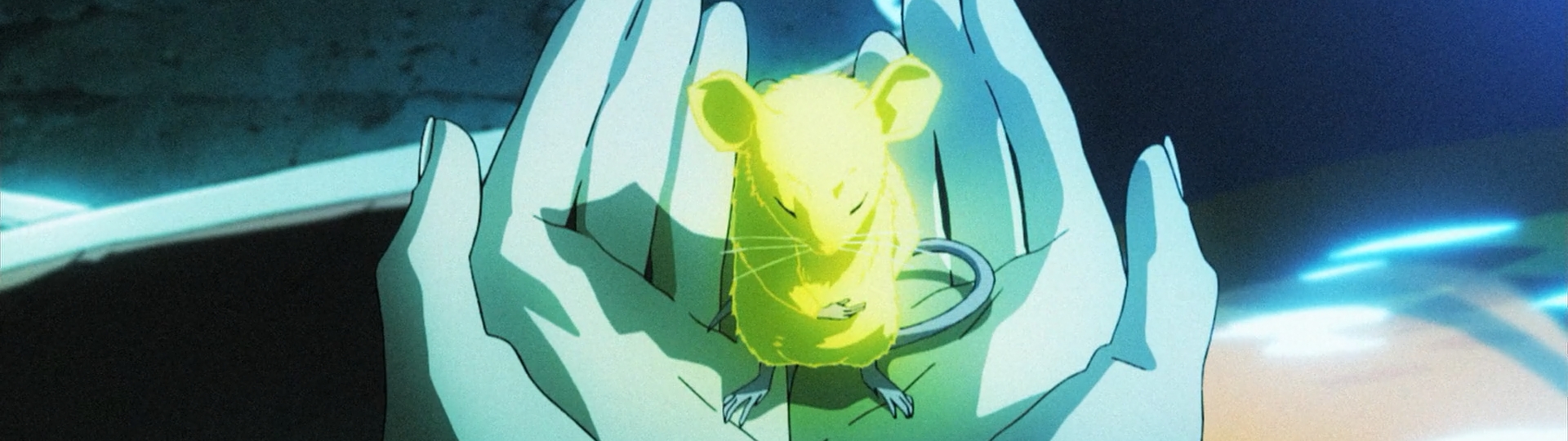

In this hidden world, Haruka meets Teo, a rabbit-like youngster who’s part of a large group assigned with the task of retrieving items from the human world. Teo woefully under-performs, and is mocked and bullied by his peers for his lack of prowess. Everyone here is at the service of a dictator known as the Baron, a burly and effeminate character who lives in a flamboyant airship that hovers over Oblivion Island. The Baron has an invested interest in collecting mirrors—particularly the fine one Haruka possessed—as they’re said to embody great powers.

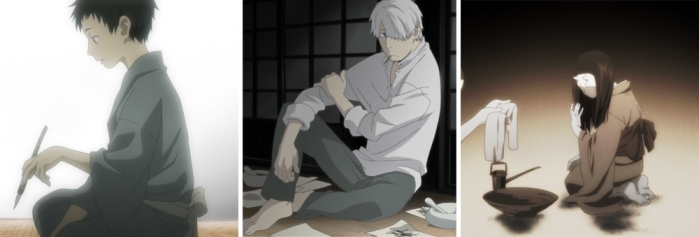

There are a lot of strong feelings about the use of computer animation in anime. Some people hate 3D with the passion of a thousand suns, while others don’t care, or may not even notice how it differs from traditional mediums. Typically, hand drawn animation reflects the personal and inexact touch of a human artist, while computer animation combines art with technology to potentially create detailed and photorealistic imagery. In recent years, toon-shaders, a rendering method that strips down lighting details to emulate a 2D look, have gained popularity.

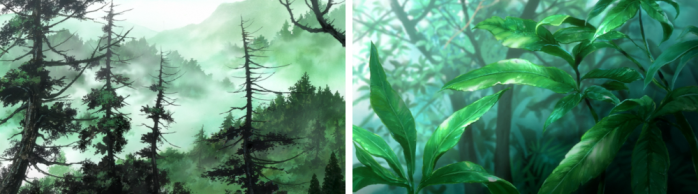

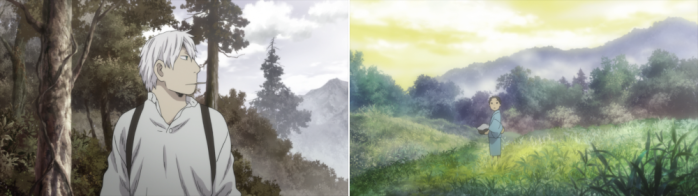

For Haruka and the Magic Mirror, Production I.G.—under the supervision of writer, director, and video game developer Satou Shinsuke—went for a more complete 3D look. The characters are fully shaded with soft shadows and indirect lighting, and their mouth movements are synced to the syllables of the Japanese voice acting. The environments and vehicles of Teo’s world are an assemblage of the countless items taken from the human world, creating a really cool patchwork aesthetic. The backgrounds have a unique quality to them as well, and appear to have utilized a mix of hand painted and 3D techniques.

Haruka and the Magic Mirror is a family movie with a simple story and characters that are fitting for its target audience. There are some dark moments that could be troubling for a pretween, but there’s no strong sexual or violent content. The finale went a little overkill on the action; this wasn’t necessarily an issue for me personally as I kind of enjoyed the mess. On the whole, the fantastic art direction, wild action set pieces, and a sweet story about family, friendship, and gratitude provided adequate entertainment value.

On June 12th, 1929, about ten-years before the start of World War II, Annelies Marie Frank was born to parents Otto and Edith Frank in Frankfurt, Germany. Rendered stateless by the Nazis in 1941, and without any means to flee the country, Anne and her family were forced into confinement for two-years in a cramped attic to avoid persecution. While staying there, Anne documented her life in a now famous diary, which has since been adapted into movies, plays, and even an anime.

On June 12th, 1929, about ten-years before the start of World War II, Annelies Marie Frank was born to parents Otto and Edith Frank in Frankfurt, Germany. Rendered stateless by the Nazis in 1941, and without any means to flee the country, Anne and her family were forced into confinement for two-years in a cramped attic to avoid persecution. While staying there, Anne documented her life in a now famous diary, which has since been adapted into movies, plays, and even an anime.